Recent fossil discoveries have lead scientists to believe

that some prehistoric animals were venomous. Gong et al. (2010) hypothesized that Sinornithosaurus,

a bird-like raptor, used venom to subdue its prey. Upon examination, the

fossilised skull was found to have grooves in the teeth and pits in the

jawbones. The maxillary teeth of Sinornithosaurus

are unusually long, and are morphologically similar to those of ‘rear-fanged’

snakes. It is suggested that the venom travelled in ducts to the bases of the

teeth, where it mixed with saliva. Sinornithosaurus

probably fed on birds and small mammals. The long front teeth were not deeply

inserted into the prey, as their length inhibits bite force. Instead, the long

teeth were used to penetrate the thick layer of birds’ feathers and then pierce

the skin, allowing envenomation to occur. The shallow depth of the wound

allowed venom to enter the bloodstream, but was not deep enough for the prey to

die from trauma. This suggests that the Sinornithosaurus’s

venom placed its prey into a state of shock (Gong, et al., 2010).

A guess of what Sinornithosaurus looked like (Image 1).

Sinornithosaurus skull showing grooves and pits in the teeth and jaws (Image 2).

In Alberta, Canada fossilised remains of a North American

mammal, Bisonalvus browni (thought to

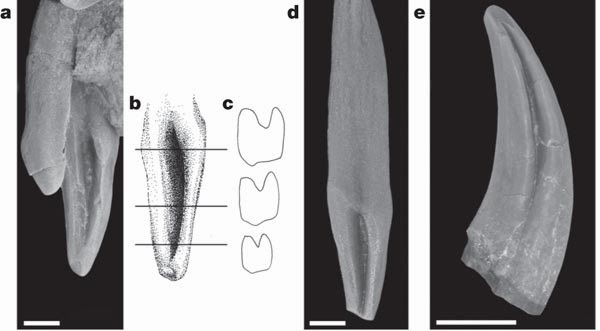

be related to pangolins and shrews), show similar grooves in the teeth. The

upper canines of B. browni are

modified to form a venom-conducting tooth. The crowns are elongated and

dagger-like, with a sharp point. The

anterior sides of the canines are much broader, and are subdivided by a deep

groove that extends from the base of the teeth to the tips. It is known that

this feature is not caused by post-mortem exposure and damage, as the walls of

the groove are covered in enamel. These grooves are also found in the canines

of other B. browni specimens, so it

is not a morphological deformity. Fox and Scott (2005) suggest that this groove

acted like a gutter, conducting venom from glandular tissue in the upper jaw to

the tip of the canine. This would allow B.

browni to inject venom into prey as it bit it. A similar structure can be

seen in Solenodon (a shrew found in Cuba and Mexico). The lower second incisors

are enlarged and the crowns of the teeth are deeply grooved, serving as a

specialised structure for the concentrated delivery of venom (Fox & Scott,

2005) .

The grooves in the canine teeth of Bisonalvus browni (Image 3).

A Solenodon (Image 4).

Fox and Scott (2005) suggest that many other prehistoric animals (particularly mammals) may be venomous. So, who knows, maybe Scrat is actually a very dangerous animal.

(Image 5).

References

Fox, R., & Scott, C. (2005). First evidence of a

venom delivery apparatus in extinct mammals. Nature, 435,

1091-1093.

Gong, E., Martin, L., Burnham, D.,

& Falk, A. (2010). The birdlike raptor Sinornithosaurus was venomous. PNAS

, 107 (2), 766-768.

Images

Image 2 - http://scienceblogs.com/notrocketscience/wp-content/blogs.dir/474/files/2012/04/i-3d67498abe3aca4f908516191c3fa3e1-Sinornithosaurus-skull.jpg. Accessed on 14/3/14.

Image 3 - http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v435/n7045/images/nature03646-f2.2.jpg. Accessed on 14/3/14.

Image 4 - http://www.culturequest.us/cuba/animallife_files/cubansolenodon.jpg. Accessed on 14/3/14.

Image 5 - http://images.wikia.com/scrat/images/e/e7/Scrat_(2).jpg. Accessed on 14/3/14.

Image 5 - http://images.wikia.com/scrat/images/e/e7/Scrat_(2).jpg. Accessed on 14/3/14.

.jpg)

It’s great that morphology can tell us so much about the behaviour of prehistoric animals! It’s also interesting that the use of venom is so widespread, even historically. I’m not sure I agree about the dangers of Scrat :) Do you know around what time venom appears in the fossil record?

ReplyDeleteNone of the articles I've read have mentioned a specific time frame. Fox and Scott (2005) noted that some fossils with similar features to the ones I mentioned (longer teeth, grooves and pits) might have been overlooked because no one thought that prehistoric animals were venomous. And obviously the organic tissue isn't preserved, so no one can completely confirm that these features were used to inject venom into prey. I'll have a look at a few other articles though, it'll be interesting to find out.

DeleteThis is an interesting blog. I've never even given any thought to the idea that prehistoric animals could be venomous. I'm curious what other animals could have also been venomous now. I love the pictures provided in your blog as well!

ReplyDeleteThanks Amanda. It's very interesting to think about what we don't know about prehistoric animals.

ReplyDeleteYou made such an interesting piece to read, giving every subject enlightenment for us to gain knowledge. Thanks for sharing the such information with us to read this.

ReplyDeleteVenom OG Strain